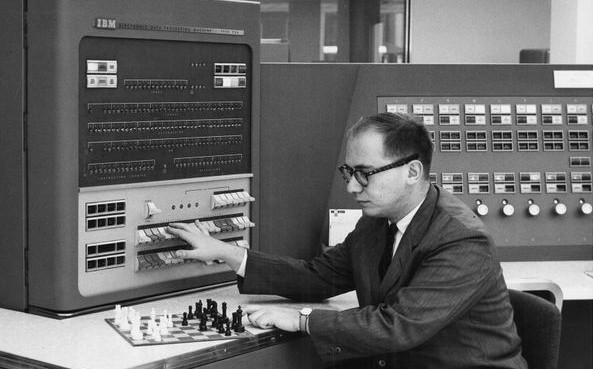

Alex Bernstein playing chess on an IBM 704

Computers ushered an era of information processing that seems to have no end. Today, the cloud is the new mainframe, the place of big data processing. The latest developments include shifting some workloads to the edge, where data is generated e.g. on Smartphones and industrial IoT gateways. Web3 attempts to codify “decentralized” trading operations of crytpoassets. Computer models of physical objects and processes are being packaged as “digital twins” to represent and control through advanced dashboards. The Metaverse could blend massive social networks with augmented reality and Niantic Labs-like experiences. Are we aiming for a replica of everything inside the compute fabric as software is eating the world?

Back to Where it Began

The year is 1958 and Bernstein is sitting in front of the Type 704 Electronic Analytical Control Unit, one of over 10 pieces of peripheral equipment making up the complete vacuum tubes-based IBM mainframe.

Dwight Eisenhower is the president of the United States of America and IBM is working on the transition from vacuum tubes to transistors as well as replacing cathode-ray tube with magnetic-core memory. The first model will be the 7070 followed by the 7090 [1]. The memory of the 704 is 32,768 words where 36 bits make up one word. It supported floating-point arithmetic and indexing which lets the programmer make use of subroutines.

I was intrigued earlier this summer reading about Alex Bernstein’s involvement in Simulmatics and the early use of IBM mainframes in Jill Lepore’s IF THEN [2] which tells the story of The Simulmatics Corporation. A company founded by a group of men who saw the potential of applying computational approaches to social sciences that may have been the first startup saga from Minimum Viable Product in 1959 to bust in 1970.

From Chess to Macroscopes

As it turns out, Bernstein was one of the initial Simulmatics team members along with William N. McPhee, Ithiel de Sola Pool, and Robert Abelson. McPhee, a Columbia sociologist, was one of the first who had the idea to evaluate public survey data using computers and seeking ways to scale investigations from the individual level to mass electorates. His initial work in the fifties sparked a long series of approaches including the Michigan model that would supercede his voting choice model, political culture models in the sixties, system dynamics in the seventies, social influence models in the following decade, bottom-up and artificial society models in the nineties, and political cognition followed by social complexity models after 2000.

The Columbia model of political attitudes and voting choices is based on the concepts of social context and local interpersonal communication networks. The school’s main hypothesis was that electoral media and campaigns had only ‘minimal effects on individuals’ voting behaviour. Instead, voting choices are shaped by social context captured by connections between two voters, also known as dyads in social network analysis. Below is a very brief outline from [3] on the three-step design.

- the stimuli perception by the individual voters made of pairwise interactions and mass media messages leading to voting predispositions;

- the update of the variables describing the individual’s political interest level and attitutde attributes based on voter interactions;

- the learning/forgetting of the stimuli perceived during the electoral campaign.

The input stimuli were simulated by a distribution of values based on preliminary sociometric measurements. The three processes are chained and feed back political influence onto new predispositions achieving dynamic behavior. The outcome of a run consisted of an updated distribution of voting choices. Aside from incorporating social influence, McPhee’s implementation incorporates scaling individual perceptions and the Monte Carlo method of random sampling from distributions of political attitudes.

The Columbia school of thought was characterized by a small worlds view in which voters influence each other through family, friends, co-workers. IF THEN goes on to mention de Sola Pool’s key role in advancing the idea of small world experiments leading up to Milgram’s famous experiment and “six degrees of separation.” The declining quality of reports produced by Simulmatics and its involvement in the Vietnam war would eventually lead to its downfall. Student protests at MIT accused the company of war crimes and a mock trial of de Sola Pool was held in 1969.

McPhee’s Voting Choice model was originally designed to run on an IBM 650 which was a serial, decimal, stored-program mid-range computer announced in July 1953. The hot new addition was its magnetic disk unit and terminals for query and response applications. These I/O additions made it differ from card-processing systems. Its successor would be the transistorized IBM 7070.

At the time, Abelson was Professor of Psychology at Yale and de Sola Pool Professor of Political Science and Director of the International Communication Program of the Center for International Studies at MIT. Abelson and de Sola Pool worked with McPhee to apply the Voting Choice Model to survey data of over 85,000 respondents. The massive data set encoding survey data (we would say Big Data today) was reduced to a matrix of 480 rows of voter types and 52 columns correspondng to empirical social structure data. If my understanding of the model is right, it would have been extended with predisposition (direction, intensity), political interest and voting choice columns for the simulation runs.

The Simulmatics If-Then-Men quickly recognized the value of their political “data bank” and used it to identify insights on African American voters in the North of the country in 1960. This included statements such as, for example, that anti-catholicism was less prevalent among African Americans in comparison with urban, protestant whites [4]. The report was made available to the Democratic National Committee whose candidate, John F. Kennedy, would defeat Richard Nixon in November that year. Simulmatics would later offer similar services to a wide range of organizations, including public and private.

Its involvement extended into the Vietnam war participating to the massive data gathering effort put in place to handle compexities of small-unit jungle combat managed from the distant United States of America. Survey data gathered and encoded included body counts, bomb tonnage, percentage of the population loyal to the South, patrols performed, “pacified” hamlets [5]. The Vietnam is the apotheosis of closed-world politics according to Edwards. His definition of closed-world is a bounded scene of conflict. An inescapable self-referential space where every thought and action is directed back toward a central struggle.

Today’s People Machines

In her book IF THEN, Lepore tells the backstory of the first People Machine and draws a link forward in time to Cambridge Analytica. While it is certainly a recent endeavor in applied social network analysis to big data in the tradition of Simulmatics, there are other projects out there that also pursue the same spirit of applying math at scale to understand complex societal issues.

Without applying judgement or drawing an explicit link, I would just like to give a couple of examples which luckily do not present the nefarious side of Cambridge Analytica. Professor Alex ‘Sandy’ Pentland heads the MIT Connection Science initiative. His views on how big data can help build a better world share some of McPhee’s local network influence ideas. Pentland has comparatively access to an incredible array of data sources that the If-Then-Men could only dream of. This includes Smartphone data. Pentland, contrary to McPhee and traditional social modelers, taps into a class of models based on physics such as Ising’s model of ferromagnetic fields.

Another example is Professor Helbing’s FuturICT project that, as Simulmatics, proposed a Manhattan-like project to study the way our living planet works. In its second incarnation, FuturICT aims to provide the basis for large-scale simulations in different domains of the social sciences, aimed at advancing the current understanding of the behavior of large communities of people, especially of groups of people having different cultures, values, norms coming in contact with each other.

I find simulations fascinating and a core element of explicative programming in citizen sensing. Citizens can engage in data harvesting using their five senses or devices to acquire ground truth data and use it in simulations to better understand e.g. social or environmental phenomena. I am less thinking about mass harvesting and more about local communities trying to make sense of challenges in their environment. I am also conscious of the enormous responsibility and need to watch out for those tempted of exceeding limits we set ourselves as society. Efforts in ethical use of computing are thus essential.

Escaping the Closed World Trap

Back to Simulmatics. I enjoyed Lepore’s book for exposing an early data science startup at a time when there were no MacBooks and people like Alex Bernstein and Bill McPhee had the chops to implement Monte Carlo simulations in assembly language. The story echoes with Edwards’ book whose idea of closed-world could be considered in a context where cold war narrative is replaced with the modern polarized discourse on modern social media. Growing interest in digital twins and the Metaverse on top of social networks require us to remain vigilant with data-driven projects as our real world is burning at several platenary boundaries.

Edwards opposes closed-world to Green World - an unbounded natural setting such as a forest, meadow or glade (ironically, these could be simulated today.) Edwards’ book titled The Closed World, as a way to frame history of computing machines, is an important read today as we keep pushing the envelope of what’s possible with computing. We have the choice to shape that new frontier in a way that gives us more freedom and time in this very real world to properly adjust our respective ecological footprints and rein planetary boundaries back into acceptable limits. Let’s not make the real world, a place we prefer escaping for some online fantasy, as fascinating as its simulation may be.

References

[1] The Architecture of IBM’s Early Computers, Basche et al., Sep. 1981, IBM Journal of Research and Development., Vol. 25 No. 5

[2] IF THEN, Lepore, Sep. 2020, Liveright

[3] Political Attitudes, Voinea, 2016, Wiley

[4] The Simulmatics Project, de Sola Pool and Abelson, 1961, The Public Opinion Quarterly, Vol. 25 No. 2

[5] The Closed World, Edwards, 1996, The MIT Press

This material is licensed under CC BY 4.0

This material is licensed under CC BY 4.0