Photo by Paul Vladuchick

Earlier this week, the tweet below popped up in my timeline. A now too frequent reminder of the turbulent times we are in. France and #GiletsJaunes, UK and #Brexit, US or #MAGA. Despite living in a Western World of extreme connectivity and instantaneous access to information, we increasingly struggle to agree. We struggle even to share a common understanding of the problem. Is technology facilitating the convergence of some groups towards overly simplistic views?

Damning stuff in today’s Lancet.

— Dr Rachel Clarke (@doctor_oxford) February 26, 2019

*Every* Brexit scenario will be worse for our health:

🔹depleting NHS workforce

🔹jeopardising drug supplies

🔹risking our vaccines & devices

So just stop playing games that risk lives, @theresa_may. It’s disgusting.https://t.co/TxjZA53N17

Incidentally, I had come across a post on the importance of transdisciplinarity by Mieke van der Bijl. In her post, Mieke stresses that how we work together is no less important than how we think about the problem we try to address. I was first confronted with the notion of transdisciplinarity during my course in sustainable development. Transdisciplinarity implies crossing of boundaries. Sustainable development entered the scene in 2002 or ten years after the Earth Summit in Rio. It was going to be a new kind of development with its Venn diagram representations reflecting an approach to aligning disciplines that would stop short of transdisciplinarity.

Certainly, problems raised by Brexit or sustainable development (SD) for that matter are complex in nature. Consider the nine planetary boundaries identified by Johan Rockström and his team and connecting policy changes to address them in time. Mieke devotes a portion of her post to complexity science and mentions a particular framework to solve complex problems such as the impact of Brexit on the British healthcare system. For a visual overview of complxity science and its roots in self-organization and emergence, refer to Brian Castellani’s impressive map.

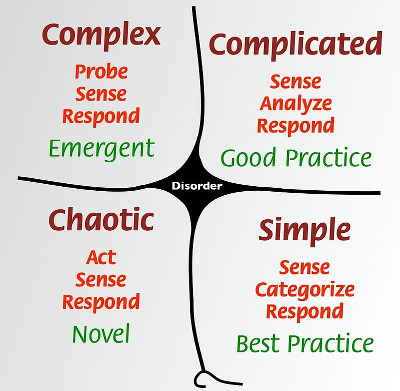

Cynefin

Complex problems come with many many constraints, many many factors and are not exclusive to sustainable development. Ask Theresa May or Emmanuel Macron. Contrast with complicated problems where we manage to identify a relationship between cause and effect through analysis. Complex problems demand experimentation. Cynefin is a framework by Cynthia Kurtz and David Snowden shown in its 2011 version below. The word comes from Welsh and is to be “understood as the place of our multiple affiliations, the sense that we all, individually and collectively, have many roots.”

Kurtz and Snowden had introduced Cynefin in the IBM Systems Journal back in 2003 under the title “The new dynamics of strategy: Sense-making in a complex and complicated world”. The framework is used e.g. in education, development and management. As its Welsh etymology suggests, it defines different perspectives and accomodates different and incompatible narratives which makes it versatile across very different situations and organizations. Constraints in Cynefin can be of different types. Governing contraints are context-free (e.g. rules) while enabling constraints are context-sensitive (e.g. heuristics). The latter bring self-organizing capabilities. Snowden recognizes humans are better at avoidance of failure than at imitation of success: defining negative boundaires will work better than defining goals as we learn best through failure. Cynefin is considered by its authors as a sense-making framework and is intended to help people break out of old ways of thinking. Constraints are identified by Cynefin folks through narrative mapping.

It seems Kurtz and Snowden parted ways back in 2007. Kurtz has since introduced “Participatory Narrative Inquiry” to describe her approach to sense-making. She has also released a new iteration of an open source software tool called NarraFirma to support participatory story work. Kurtz had previously been involed with Snowden’s SenseMaker and several other support tools. NarraFirma “helps people gather stories from a community or organization and make sense of them to inform and improve collective decision making.”. Other sense-making approaches out there include Appreciative Inquiry, VPEC-T, or IBIS.

Anyway, back to Cynefin and the tweet above. The Brexit situation is the result of a narrative construct which turned into constraints through an intricate web of self-reinforcing feedback loops. There are no case studies for these situations. How often do we hear we are in “unknown territory”? Learning by case studies only gives us limited rear-view mirror abilities. A sense-making framework is preferrable to make a situational assessment and map the territory of options.

Somehow, despite having access to potent sense-making approaches, we are still unable to share a common view of the challenges we are facing.

What’s missing from this picture?

I had turned last week to some folks on Twitter including seasoned enterprise architects @CyberSal and @tetradian who by virtue of their work face complex situations in large private and public organizations. They are familiar with Cynefin and several other models and frameworks to help their clients. Tom Graves was reminded of a post he wrote on policy-based evidence and the danger of reasoning in simple, singular causal relationships. Cause-effect relations are a big hit in our Western cultures and we are easily trapped in the idea there a reason for everything. This trap is referred to as attribution error and was also caught by @tomfid in a recent post.

In a system with delays, feedback and nonlinearity, dynamic complexity separates cause from effect. If things are sufficiently confounded, we can no more understand the system through retrospective pattern matching than we could a priori.

Tom Fiddaman is CTO at Ventana Systems, maker of Vensim, and expert in System Dynamics. Despite having introduced models referred to as Causal Loop Diagrams or CLDs, it would be naive to claim it is causal. Even simple SD models can display dynamic complexity that make this approach a compeling candidate for capturing shared models of understanding. Software such as Vensim helps to make sense of the intricate and subtle web of connections in CLDs. Emergence, as complexity science understands it, can be seen in Agent-Based Models. Simulation tools for these models support recurrent coordination of interactions among agents. The agents are programmed to adhere to certain constraints and usually, a certain behavior emerges from the simulation.

I have previously written about the use of SD by folks such as Krystyna Stave for adapting policies in water supply-and-demand, municipal waste, mobility and air quality. Software such as Vensim can make interacting with SD models entertaining. SimCity is perhaps another example of how SD can be applied for decision making while avoiding catastrophic outcomes in city mismanagement. Similarly, ABM software is used in Companion Modelling role playing games. Will we one day subject election candidates to such simulation environments? Does that even make sense? I recall FuturICT and its ambition to build a gigantic Sims game, a sort of Large Hadron Collider of social sciences. As it stands in my mind, and as Tom Fiddaman said in his post, “modelling is not optional.” We must make a better effort to understand systems and share this understanding.

Mieke’s work in transdisciplinary innovation will be essential to bring the requisite process skills in combination with institutions able to bootstrap our march towards sharing models of understanding. Good luck to us as time may not be on our side.

This material is licensed under CC BY 4.0

This material is licensed under CC BY 4.0