MIT Media Lab Lego City by kirainet

The Responsive City is a book by Stephen Goldsmith and Susan Crawford published in August last year. It tells a number of stories from Boston, New York, Chicago, Rio de Janeiro, Austin, or Chennai where city leaders have looked at challenges horizontally across departments, involved digital advocates to collaborate with ordinary citizens and empowered their fellow city workers departing from traditional public service duties & mandates.

The book contains many examples of citizen sensing applications such as the famous Boston 311 Citizen Connect or uses of the LocalData app.

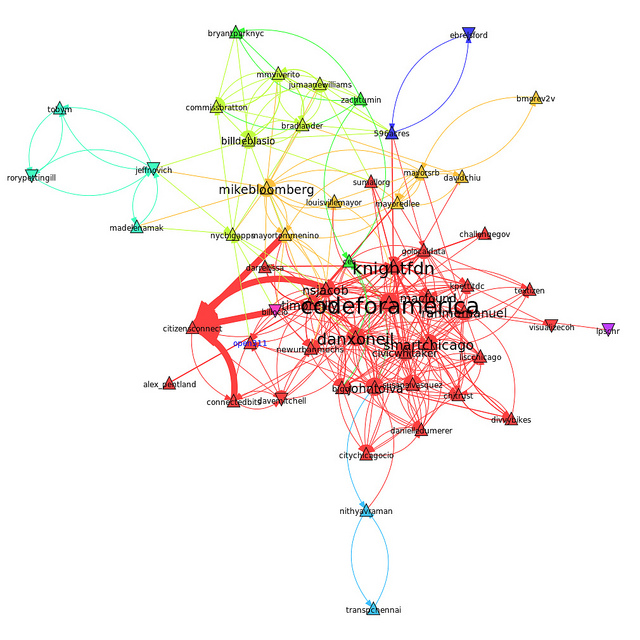

It shows the role of important North American digital advocates in the civic space such as Connected Bits or Code for America which have become recognized talent pools for civic tech. I took a partial Twitter snapshot of the individuals and organizations mentioned.

I’ll ignore here the meaning of the triangles and width of lines. Arrows represent a follow relation on Twitter. Europe is missing from this picture and from the book. You may recognize a cluster of city mayors which play a key role in driving efforts in their respective organizations. They are flanked by CIOs who are tasked with the digital transformation of the city. These guys face a number of challenges including missing/partial enterprise architecture views, convoluted procurement processes and difficult collaboration across jurisdictional boundaries. Having prescriptive procurement processes in the context of rapidly evolving consumer demand and technology is a real challenge. The example of Challenge.gov sets the stage for a lighter process which does not assume that the government brings the solution and merely looks for an execution partner…

Citizen sensing is greatly facilitated in Responsive Cities which understand the importance of data and simultaneously the involvement of citizens in various aspects of city life. There’s a wide range of examples from the usual pothole/311 but also vacant lots, health, mobility, applying for benefits, software application testing, or participatory budgeting. But the authors also looked at the flip-side of a 311 app and how city workers also benefit from personalized access to a common data set. This worker app brings new forms of participation (e.g. through rankings) as well as collaboration with supervisors.

But it’s not just citizen sensing. Open data and the use of sensors also plays a key role in the Responsive City. The book brings examples from Chicago which seems to be leading on these fronts. The city has plans to add 400 non-privacy invasive sensors in secure, boxed locations for academia, companies or government use to explore heat, light, noise and movement in the city and solve urban problems. I had come across the Array of Things which I believe is part of the program and gives some more details about this fascinating project. Open data is institutionalized so that agencies can drive rather than waiting from top-down triggers.

Training of city workers in technology is generally recognized as a challenge. Digitally-savvy intermediaries (e.g. #NerdHerd in Chicago) are bringing expertise not just in sensors but also in neogeography, social media, mobile applications and open data. What’s important, stresses one of the protagonists, is for technologists is not to pretend to know/understand the data better than experts. Their role is to bring up interesting views of the data and potential correlations which may be worth exploring.

But it’s by no means a technology play for city leaders - starting with a local strategy remains crucial for success (de Cristo, Vasquez). The authors give examples of mechanisms used by cities to work with grassroots organizations such as Social Impact Bonds i.e. pay-for-success contracts and Business Improvement Districts. Perhaps B corporations and the great example of Azavea would have also been worth mentioning here. Azavea is a geospatial analysis talent pool which deploys its skills in big data and mapping to help its clients improve their communities in a sustainable way.

I have argued previously that the usual top-down vs. bottom-up debate so common in the “Smart City” context is perhaps more a clue that a paradigm needs to be dissolved, re-framed. While The Responsive City clearly shows the key role mayors play in re-shaping their organization, it also leads one to explore further the governance aspects taking place at various scales throughout the urban ecosystem considered.

The shift away from command-and-control facilitated by data in combination with greater distribution of discretion across the organization is perfectly aligned with a Viable Systems approach. I still believe there’s lots to learn from this model which operates at multiple levels of recursion in a way where functional discretion is explicitly considered and distributed to people or groups which control the use of the resources to accomplish the function. The model embraces the fact that management has over time evolved from Taylor’s view to one which acknowledges multi-faceted, intertwined situations where people at the local level have the requisite autonomy to satisfy constituents. Rolling up the same principles, level after level.

I wish I could provide equivalent pointers in Europe but haven’t found the time to do so. A good starting point, would be to scout EU Smart Cities and Communities and join Olga Gil’s G+ community on Smart Cities. Thank you Lily for pointing this book out to me!

This material is licensed under CC BY 4.0

This material is licensed under CC BY 4.0